Medical Marijuana Study

Emerging Clinical Applications For Cannabis & Cannabinoids

A Review of the Recent Scientific Literature, 2000 — 2015

Humans have cultivated and consumed the flowering tops of the female cannabis plant, colloquially known as marijuana, since virtually the beginning of recorded history. Cannabis-based textiles dating to 7,000 B.C.E have been recovered in northern China, and the plant’s use as a medicinal and mood altering agent date back nearly as far. In 2008, archeologists in Central Asia discovered over two-pounds of cannabis in the 2,700-year-old grave of an ancient shaman. After scientists conducted extensive testing on the material’s potency, they affirmed, “[T]he most probable conclusion … is that [ancient] culture[s] cultivated cannabis for pharmaceutical, psychoactive, and divinatory purposes.”

Modern cultures continue to indulge in the consumption of cannabis for these same purposes, despite a present-day, virtual worldwide ban on the plant’s cultivation and use. In the United States, federal prohibitions outlawing cannabis’ recreational, industrial, and therapeutic use were first imposed by Congress under the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 and then later reaffirmed by federal lawmakers’ decision to classify marijuana — as well as all of the plant’s organic compounds (known as cannabinoids) — as a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. This classification, which categorizes the plant by statute along side heroin, defines cannabis and its dozens of distinct cannabinoids as possessing ‘a high potential for abuse, … no currently accepted medical use, … [and] a lack of accepted safety for the use of the drug … under medical supervision.’ By contrast, cocaine and methamphetamine — which remain illicit for recreational use but may be consumed under a doctor’s supervision — are classified as Schedule II drugs; examples of Schedule III and IV substances include anabolic steroids and Valium respectively, while codeine-containing analgesics are defined by a law as Schedule V drugs, the federal government’s most lenient classification. Both alcohol and tobacco remain unscheduled.

In July 2011, the Obama Administration rebuffed an administrative inquiry seeking to reassess cannabis’ Schedule I status, and federal lawmakers continue to cite the drug’s dubious categorization as the primary rationale for the government’s ongoing criminalization of the plant and those who use it. A three-judge panel for the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia affirmed the Administration’s position in 2013, arguing that a judicial review of cannabis’ federally prohibited status was not warranted at the time.

Most recently, in April 2015, a federal judge in Sacramento upheld the constitutionality of cannabis’ Schedule I classification in a case argued by members of the NORML Legal Committee. The judge’s ruling opined that the federal law ought to remain in place as long as there remains any dispute among experts as to cannabis’ safety and efficacy.

Nevertheless, there exists little if any scientific basis to justify the federal government’s present prohibitive stance and there is ample scientific and empirical evidence to rebut it. Despite the US government’s nearly century-long prohibition of the plant, cannabis is nonetheless one of the most investigated therapeutically active substances in history. To date, there are approximately 22,000 published studies or reviews in the scientific literature referencing the cannabis plant and its cannabinoids, nearly half of which were published within the ten years according to a key word search on the search engine PubMed Central, the US government repository for peer-reviewed scientific research. While much of the renewed interest in cannabinoid therapeutics is a result of the discovery of the endocannabinoid regulatory system (which is described in detail later in this booklet), some of this increased attention is also due to the growing body of testimonials from medical cannabis patients and their physicians.

The scientific conclusions of the overwhelmingly majority of modern research directly conflicts with the federal government’s stance that cannabis is a highly dangerous substance worthy of absolute criminalization.

For example, in February 2010 investigators at the University of California Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research publicly announced the findings of a series of randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials on the medical utility of inhaled cannabis. The studies, which utilized the so-called ‘gold standard’ FDA clinical trial design, concluded that marijuana ought to be a “first line treatment” for patients with neuropathy and other serious illnesses.

Several of studies conducted by the Center assessed smoked marijuana’s ability to alleviate neuropathic pain, a notoriously difficult to treat type of nerve pain associated with cancer, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, spinal cord injury and many other debilitating conditions. Each of the trials found that cannabis consistently reduced patients’ pain levels to a degree that was as good or better than currently available medications.

Another study conducted by the Center’s investigators assessed the use of marijuana as a treatment for patients suffering from multiple sclerosis. That study determined that “smoked cannabis was superior to placebo in reducing spasticity and pain in patients with MS, and provided some benefit beyond currently prescribed treatments.”

A summary of the Center’s clinical trials, published in 2012 in the Open Neurology Journal, concluded: “Evidence is accumulating that cannabinoids may be useful medicine for certain indications. … The classification of marijuana as a Schedule I drug as well as the continuing controversy as to whether or not cannabis is of medical value are obstacles to medical progress in this area. Based on evidence currently available the Schedule I classification is not tenable; it is not accurate that cannabis has no medical value, or that information on safety is lacking.”

Around the globe, similarly controlled trials are also taking place. A 2010 review by researchers in Germany reports that since 2005 there have been 37 controlled studies assessing the safety and efficacy of marijuana and its naturally occurring compounds in a total of 2,563 subjects. By contrast, many FDA-approved drugs go through far fewer trials involving far fewer subjects. In fact, according a 2014 review paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the median number of pivotal trials performed prior to FDA drug approval is no more than two and over one-third of newly approved pharmaceuticals are brought to market on the basis of only a single pivotal trial.

As clinical research into the therapeutic value of cannabinoids has proliferated so too has investigators’ understanding of cannabis’ remarkable capability to combat disease. Whereas researchers in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s primarily assessed cannabis’ ability to temporarily alleviate various disease symptoms — such as the nausea associated with cancer chemotherapy — scientists today are exploring the potential role of cannabinoids to modify disease.

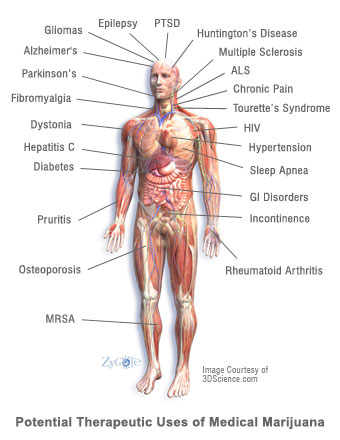

Of particular interest, scientists are investigating cannabinoids’ capacity to moderate autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as their role in the treatment of neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (a.k.a. Lou Gehrig’s disease.) In 2009, the American Medical Association (AMA) resolved “that marijuana’s status as a federal Schedule I controlled substance be reviewed with the goal of facilitating the conduct of clinical research and development of cannabinoid-based medicines.”

Investigators are also studying the anti-cancer activities of cannabis, as a growing body of preclinical and clinical data concludes that cannabinoids can reduce the spread of specific cancer cells via apoptosis (programmed cell death) and by the inhibition of angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels).

Researchers are also exploring the use of cannabis as a harm reduction alternative for chronic pain patients. According to the findings of a 2015 study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, a non-partisan think-tank, “[S]tates permitting medical marijuana dispensaries experience a relative decrease in both opioid addictions and opioid overdose deaths compared to states that do not.” The NBER findings are similar to those published in 2014 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Internal Medicine which also reported that the enactment of statewide medicinal marijuana laws is associated with significantly lower state-level opioid overdose mortality rates. “States with medical cannabis laws had a 24.8 percent lower mean annual opioid overdose mortality rate compared with states without medical cannabis laws,” researchers concluded. Specifically, they determined that overdose deaths from opioids decreased by an average of 20 percent one year after the law’s implementation, 25 percent by two years, and up to 33 percent by years five and six.

Arguably, these recent discoveries represent far broader and more significant applications for cannabinoid therapeutics than many researchers could have imagined some thirty or even twenty years ago.

THE SAFETY PROFILE OF MEDICAL CANNABIS

Cannabinoids possess a remarkable safety record, particularly when compared to other therapeutically active substances, particularly prescription drugs. Most significantly, the consumption of marijuana — regardless of quantity or potency — cannot induce a fatal overdose. According to a 1995 review prepared for the World Health Organization, “There are no recorded cases of overdose fatalities attributed to cannabis, and the estimated lethal dose for humans extrapolated from animal studies is so high that it cannot be achieved by … users.”

In 2008, investigators at McGill University Health Centre and McGill University in Montreal and the University of British Columbia in Vancouver reviewed 23 clinical investigations of medical cannabinoid drugs (typically oral THC or liquid cannabis extracts) and eight observational studies conducted between 1966 and 2007. Investigators “did not find a higher incidence rate of serious adverse events associated with medical cannabinoid use” compared to non-using controls over these four decades.

That said, cannabis should not necessarily be viewed as a ‘harmless’ substance. Its active constituents may produce a variety of physiological and euphoric effects. As a result, there may be some populations that are susceptible to increased risks from the use of cannabis, such as adolescents, pregnant or nursing mothers, and patients who have a family history of psychiatric illness. Patients with a history of heart disease or stroke may also be at a greater risk of experiencing adverse side effects from marijuana. As with any medication, patients should consult thoroughly with their physician before deciding whether the medical use of cannabis is safe and appropriate.

HOW TO USE THIS REPORT

As states continue to approve legislation enabling the physician-supervised use of medical marijuana, more patients with varying disease types are exploring the use of therapeutic cannabis. Many of these patients and their physicians are now discussing this issue for the first time and are seeking guidance on whether the therapeutic use of cannabis may or may not be advisable. This report seeks to provide this guidance by summarizing the most recently published scientific research (2000-2015) on the therapeutic use of cannabis and cannabinoids for a variety of clinical indications.

In some of these cases, modern science is now affirming longtime anecdotal reports of medical cannabis users (e.g., the use of cannabis to alleviate GI disorders). In other cases, this research is highlighting entirely new potential clinical utilities for cannabinoids (e.g., the use of cannabinoids to modify the progression of diabetes.)

The conditions profiled in this report were chosen because patients frequently inquire about the therapeutic use of cannabis to treat these disorders. In addition, many of the indications included in this report may be moderated by cannabis therapy. In several cases, preclinical data and clinical data indicate that cannabinoids may halt the advancement of these diseases in a more efficacious manner than available pharmaceuticals.

For patients and their physicians, this report can serve as a primer for those who are considering using or recommending medical cannabis. For others, this report can serve as an introduction to the broad range of emerging clinical applications for cannabis and its various compounds.